What the Film Gattaca Taught Me About Society -- and Myself.

I remember being floored by the impact the film Gattaca had on me. I was six years out of divinity school, and though engaged in faith-based racial justice work, not feeling like I was making much headway. Nor did I understand why.

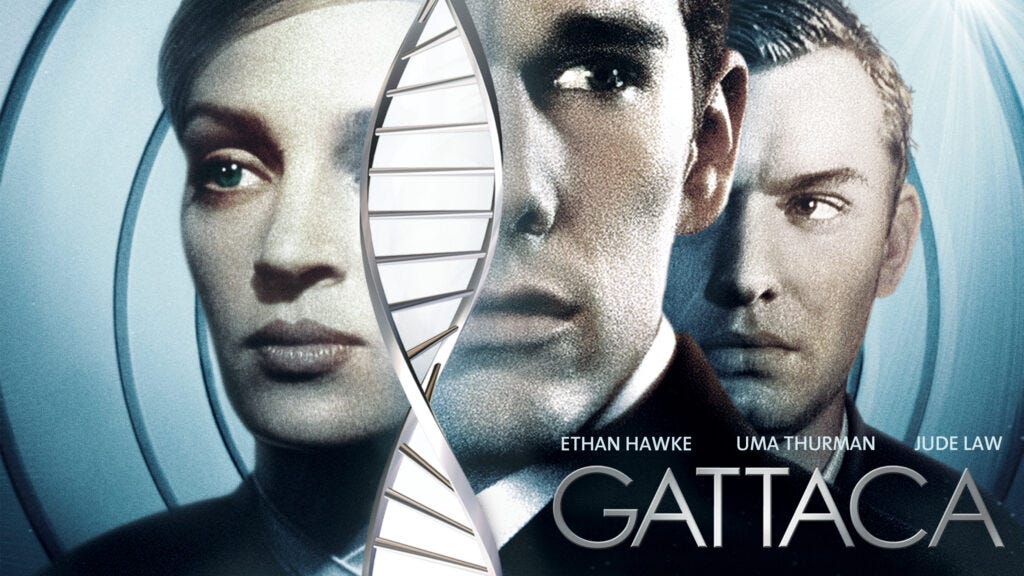

I was living in San Rafael; and my best friend Bob Jackson invited me to see a film that had been shot right there at the futuristic Marin Civic Center, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. I didn’t even know what it was about. But watching it, what stayed with me was the social structure of this future society; one based on “Invalids” and “Valids”. It was the first time I remember recognizing that our societal order is one we ourselves designed.

Realizing that ideas like race and gender, or in Gattaca’s case, genetic status, are constructs, would transform my approach to social justice, and might be the moment the perspective that’s shaped all my work since came into focus. Discovering that our sorting systems are ones that we built is both freeing and burdensome. Because if we built them, we can change them, and if we don’t change them, we share responsibility for the harm they cause.

Things I’d been told were handed down by God or encoded in our genes were, all of a sudden, easily recognizable as campfire stories. As a multiple minority, I might be considered by others to be our equivalent of an Invalid. But I’d also learned that our categories define us no better than they did Vincent, the film’s protagonist, who, due to a genetic prediction of a lifespan of 30.2 years, was someone his society had deemed inferior.

But to get my head around this, I needed to de-bias my own thinking; to get under the hood of how this even happens; how labels that have no inherent meaning, other than the status they convey or take away, come to rule us. In their world, that was “Valids” and “Invalids”. In ours, I would come to think of them as “Outsiders” and “Eligibles”.

Outsiders are those assigned to society’s underclass. In every way we can get away with, we invalidate them and disqualify them, exploit them and alienate them. They’re deprived of social agency and denied equality. They’re repeatedly told that they’re lesser, and to “mind their betters”. They’re stripped of full personhood, then, rendered mute and invisible so that they can’t complain. They’re labeled “abominations” and “terrorists” and “illegals”. They die younger and suffer more. That’s life for an Outsider.

But if you’re an Eligible, society is an entirely different place. Like American Express, membership has its privileges. Your whole life is not unlike being recognized as a “very well qualified” buyer in a car dealership. There, your business is aggressively sought after, your needs catered to, and the overall price you will pay for the car, significantly lower. You’ll be treated preferentially, spoken to deferentially, and your entire experience will be the utmost in pleasantry. Your wish is their command. Want to test drive the car alone? No problem. Want to keep it for the weekend? Sure. Want special upgrades or a vehicle that has never touched the road? Done and done.

If you’re an Eligible in America, you can go your whole life without ever being socially demoted. You can comfortably wait for your friend without being accused of loitering or expect a traffic stop to be anything more than that. Imagine that these two people are pulled over by the police and issued tickets. The Eligible says, “I can’t believe that f*%$ing cop gave me a ticket!”, whereas the Outsider would be grateful to only have gotten a ticket. Eligibles move through life with a kind of socialized luck; the experience of having more things than not fall their way.

That’s not to say that they don’t work hard for what they have. They do. At the same time, this enhanced cultural favorability acts as a force multiplier; translating into tangible rewards such as job offers, getting the apartment and being given the benefit of the doubt; which serve as experiential confirmation that the world truly is a fair place for those who apply themselves. By living in a context that has co-opted the definition of “attractiveness”, they receive all its attendant rewards. This starts early: Teachers perceive children they consider attractive as smarter, more engaged in school, and more likely to succeed academically than children deemed unattractive.

Eligibles have few, if any, derogatory nicknames (compared to the plethora of slurs invented for others), and they live in a culture that, in many ways, really does revolve around them. This is why LGBTQ+ people need to come out as different, whereas those who identify as straight do not, why we fight the use of feminine pronouns to describe God, why we don’t get how “you people” is offensive, why we’re blind to the judgment baked into terms like “overweight”, and why we fail to see how the phrase “under God” in our Pledge of Allegiance is alienating to Americans who love their country but don’t believe in a supreme being.

Eligibles have the luxury of being treated as individuals, rather than as part of a group (they’ll never be told that they’re a credit to their race/gender/faith). They can enter other social contexts (going to a historically black church, a gay bar, etc.) without penalty or reprisal, and are afforded greater leniency in encounters with the justice system. Over time, this Outsiders-Eligibles structure would emerge as our version of Gattaca’s “Invalids” and “Valids”; one able to exist and thrive right alongside democracy and equality.

But also like in Gattaca, being favored and being fulfilled are far from the same thing. Probably what surprised me most about the film was its pervasive sense of sadness and tragedy. Because every Valid we meet, in their own way, feels less than valid. Jerome, who donated the DNA samples that allowed Vincent to pass for him, was paralyzed in his attempt to take his own life. Irene, with whom Vincent falls in love, has a heart defect that prevents her from pursuing her dream of a deep space mission. Director Josef committed murder, and to a person, the Valids seem intensely lonely and hopeless.

I was reminded of a man who came to me for pastoral counseling. He had significant inherited wealth, was traditionally handsome and was well-liked. Yet, having come from a home where his parents never hugged him or told him they were proud of him, he suffered from crushing unworthiness. I couldn’t help but think of my own life with my grandmother Mary, who lavished me with love, and of my large family who, every day, made me feel like I was a gift. I know I got the better deal.

In many ways, Vincent was similar. As a byproduct of love, rather than genetic manipulation, sure, he was imperfect. But he was also extraordinary. Vincent lacked the enhancements that his brother Anton had. Yet, he not only surpassed Anton but outperformed people who were designed to be his genetic superiors.

Toward the end of the film, Ethan Hawke’s character, Vincent, beats his brother in a high-stakes open water swim; something he’d done only once in his entire life. “How are you doing this, Vincent?” Anton asks, “How have you done any of this?” Vincent says, “You wanna know how I did it? This is how I did it Anton; I never saved anything for the swim back.”

Vincent, with his humanity fully intact, would go on to win a coveted seat on the Titan space mission. He’d leave that world of Valids and Invalids behind for a place where corrosive constructs are irrelevant and where he was finally free to be the person only he could be and make the contributions only he could make.

In the end, Vincent’s story would teach me a lesson that would stay with me forever; that no label or test can determine our potential or how far in life we go. Only we can.