"We're Gonna Make It Anyway"

Election Reflections #3: Why, though some are declaring this election an ending, it has all the makings of a beginning.

A few days ago, just after the election, I had a conversation with my sister who’s an anti-poverty/homelessness activist. It started with a text from her that simply said, “What do you think of me running for mayor of Richmond?” the economically impaired California town where most of her activism and advocacy efforts are focused.

Crystal, African American, female and Southerner, who survived abject poverty as a little girl, and who, as a woman, had to bury her three sisters before they reached the age she is now, has never expressed any interest whatsoever in politics, nor is she compelled to take this on for career reasons. She’s part of a massive contingent of women of all colors who are determined to change things so that the next time a powerful woman runs, she wins. “I LOVE it!” I immediately texted back.

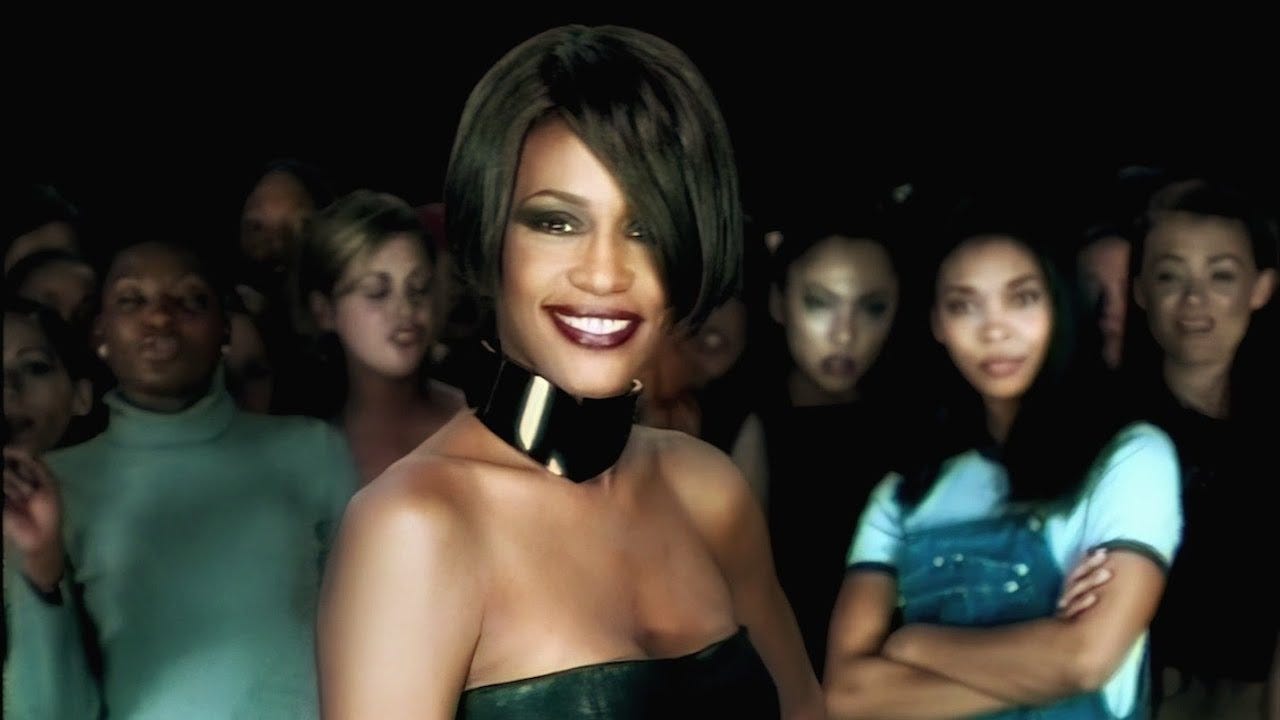

“It’s not right,” she said when we spoke later, talking our way through our swirling feelings about the election, and all of a sudden, I could hear Whitney Houston’s incomparable voice in my head completing that sentence – “But it’s okay. I’m gonna make it anyway.” And I realized that right that moment, tens of thousands of women were holding that same sentiment in their hearts.

It’s not right, but it’s okay. I’m gonna make it anyway.

They’d decided they weren’t going to believe the nonsense that twice now, America has spoken, declaring that it doesn’t want a woman president – something that sounds suspiciously like all the other things we’ve said to women – from denying them the vote to income disparity to claiming that they (or immigrants, or ethnics) “brought it on themselves”.

But they’ve also realized something powerful and liberating; that while Trump backers got their “what”, their man in office, what they don’t get to do is own our “why”. They don’t get to tell Kamala voters that they lost “fair and square” or to “accept the will of the people” – especially after the deplorable behavior on display after the 2020 election and with only 31% of the voting population backing him.

The people posting “Black lives don’t matter and neither do their votes” don’t get to blame the victims, saying that this election was lost because of some imagined mass defection of dark-skinned voters to Trump. People like a certain senator from Texas who, in 2022, after the Supreme Court struck down Roe v. Wade, tweeted, "Now do Plessy vs Ferguson/Brown vs Board of Education," don’t get to tell us that our rights aren’t in danger and not to worry, that they’re not going to dismantle democracy. They don’t get to reframe the narrative so that we, the emergent majority, are unaware of our power and blind to the – completely legal – mechanisms at play.

They don’t get to own our “why”.

That said, let me be clear. I’m not denying that their candidate won (or, rather, that he didn’t “not lose” – that’s how you outrun a bear). Nor am I going to be running around screaming, “Stop the steal!” I believe as much in our voting system today as I did when Biden won. I’m not interested in marching through the streets with loaded weapons or setting things on fire, nor will you find me traveling to DC, storming the capitol or praying for a Kamala miracle.

That’s because, for me, the problem isn’t with the votes that were cast. I don’t believe this election was “stolen” any more than the last one was. I’m challenging how we got here – the hacking of democracy that made this outcome – one where a small, ever-diminishing faction now controls every branch of the federal government - possible. He did win. I don’t doubt that. And he did so legally. I don’t doubt that either. But there’s a big difference between what’s legal and what’s right.

It’s not right, but it’s okay.

In The Way It Is? I explain that while the fatigue from years of fighting for justice no doubt put a dent in turnout for Kamala, the real problem was the gutting of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, and the subsequent disenfranchisement laws that cropped up everywhere; statutes that previously would have been illegal. But they’re not illegal anymore:

The same day of the 5-4 Supreme Court’s decision, Texas Attorney General Greg Abbott advanced a voter identification law that had previously been blocked by federal court for creating a discriminatory barrier to a fundamental right, and Alabama Attorney General Luther Strange immediately instated a similar law for the entire state.

The Brennan Center for Social Justice reported that between January and July 2021, in the wake of the failed January 6 effort to reverse the outcome of the 2020 election, eighteen states enacted laws that made it harder for certain Americans to vote. And the people behind those laws were just getting started. Since that election, 30+ states have enacted restrictive voting laws, at least 63 of which were in effect in 29 states when we voted last week.

In This Land Is Your Land, I explain it like this:

As a society built on principles of equality, the United States poses steep challenges to the development of inherited status structures; especially ones that can be maintained while still appearing to be unbiased. The key is reshaping our concept of fairness itself; which leads to social regrouping; a key tactic for any faction that wants to create (and maintain) prevailing power. The process involves breaking the collective down into subsets (segmentation), then putting it back together (reconfiguration) based on different dividing lines; leading us to form different conclusions. When applied in democracies, the resulting new majority is grounded in concrete tallies that anyone can do; which, in turn, makes the process appear fair and credible.

To get a sense of how this works, let’s say we were grouping four items; a fire engine, cherries, green beans and salsa. If you’re the fire truck, you’ll want to group by color (red), which gives you the majority. But if you’re the green beans, you’ll want to group by substance (food), which gives you the majority. The power rests with whoever selects the sorting criteria. These “fair-in-name-only” processes (FINOPs) are the social equivalents of sleeper agents; they look like one thing but are something else entirely. A plausible case can be made for their use, but practically, they correlate much more highly with a particular demographic.

Take felony disenfranchisement. Legal studies overwhelmingly expose unfairness baked into our justice system, including how two people of different ancestries or income levels can be convicted of the same crime, but receive vastly different sentences. If we’re lucky enough to be in the right group, we can literally get away with murder and not serve a day of prison time. Yet most of the fifty states still have some form of the practice on the books, and, according to the National Conference of State Legislators, 11 states strip citizens of their voting rights indefinitely, require a governor’s pardon, etc.

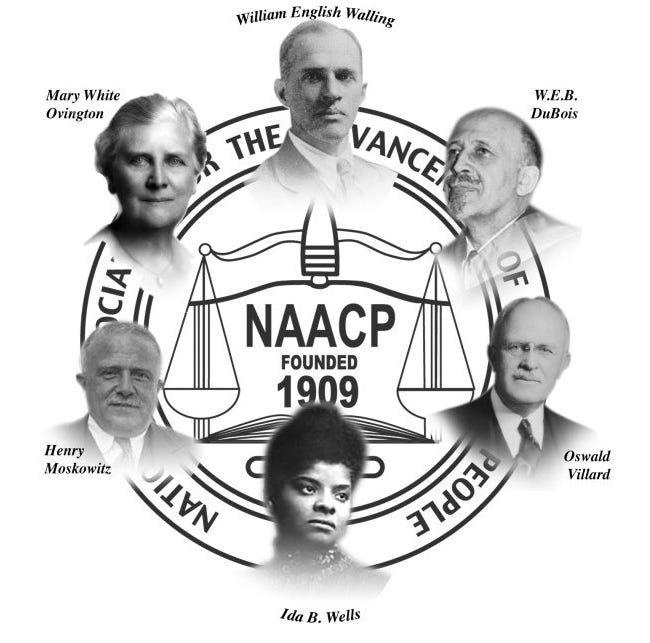

Or, take the white primaries the NAACP fought against. The idea started in 1923 when Texas Legislature passed a law that established primaries; essentially, pre-voting. Instead of denying the right to vote, they restricted who could vote in party nominations. Given the overwhelming size of the Democratic Party in the South, winning the nomination meant that the actual vote was merely a formality.

The legal case against the practice was heard by the Supreme Court four years later, with the court ruling that state laws establishing white primaries violated the Fourteenth Amendment. In response, Texas amended its law, and instead, delegated all authority to political parties to establish their own rules.

In 1935, the Supreme Court also ruled this practice illegal, as it authorized a private institution to set government policy, then, in an 8-1 decision, ruled the Texas law unconstitutional because it allowed the state Democratic Party to racially discriminate. (Notice that these were actions being taken by the Democratic, not the Republican party. Since our founding, Democrats had been the party of enslavers and segregationists. That is until the mass defection started by Sen. Strom Thurmond in 1964, leading to a takeover of the Republican party, the same party that ended slavery.)

In response, other tactics were invented and are still being invented. Texas, on the cusp of becoming minority-majority, was one of those eighteen states, starting in 2021 that enacted laws making it harder for (some) people to vote. And the Supreme Court? As the Religious Right, in 1980, started making the appointment of “Bible-believing” justices a condition for their support, SCOTUS shifted from being the lone protector of minority rights to dismantling them.

It’s not right, but it’s okay. We’re gonna make it anyway.

But all along, people have been countering this kind of behavior not just in the courtroom but outside of it.

It was in September 1965 that the fledgling United Farm Workers (UFW) effort, spearheaded by Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta, became a bona fide movement. A group of Filipino farm laborers who’d had their already low wages halved chose to strike. But in the same way that Japanese and Chinese Americans often stood apart, which made things worse for all of them, so did Mexican and Filipino farm workers, and many Mexican workers were against joining with the latter in solidarity.

That is, until Helen, Cesar’s wife, the mother of the movement, the one who went to jail for their cause the same way Martin went to jail in Birmingham, threw down the gauntlet. She challenged everyone there to either be a union for all or for none, and in doing so, she changed everything. The group did the exact opposite of what anyone profiting from oppression hopes; they joined their cause with the cause of others also being oppressed. The cheering Mexican crowd chose to expand their tent. They chose to strike.

Or, take Ferguson. To help the city begin to heal from the death of young Michael Brown, the US Justice Department launched an investigation and on March 4, 2015, released a scathing report; one concluding that the city’s police department had been routinely violating the constitutional rights of its African American members. The report demanded a complete overhaul of Ferguson’s criminal justice system.

Describing the egregious, ongoing and pervasive nature of the constitutional violations, investigators declared that the city would need to abandon its entire approach to policing, retrain its employees and establish new oversight. The implication was that the department itself had created the circumstances that made Michael’s death, or someone like him, inevitable. One of the most surprising findings was the degree to which money, rather than animus, drove many of the municipality’s abuses of power. For instance, the Justice Department found that the city of Ferguson had used both its police and courts as de facto revenue generators by targeting its most disadvantaged residents.

Representatives of both the US Department of Justice (DOJ) and the City spent months negotiating a settlement that would have prohibited police officers from making arrests without probable cause, required the installation of a DOJ representative as monitor, and barred officers from using stun guns as punishment. In response, the Ferguson City Council defiantly voted, 6 to 0, to change the terms of the settlement; knowing that the Department would take them to court.

But the one thing we should have learned from the people who instituted Black Codes and the Yellow Peril, gay hysteria and Islamophobia, is that this hubris, this delusional belief that one’s power is absolute and unending, in an ever-changing world, never works. Because those are tactics of attrition; the enemies we make will always outpace the allies we have, and eventually those who are against us will outnumber those who are for us. Which is exactly what happened in Ferguson. By the next election, those six city council seats were all filled by women, four of whom were African American.

But the example that perhaps inspires me most is that of Ann Atwater, female, African American activist in Durham, NC and CP Ellis, male, white-identifying president of the Durham KKK – bitter enemies who became best friends, and whose story is told in 2019’s The Best of Enemies. “I really began to get bitter,” said CP, reflecting back on his hard life and his path to the Klan: “I didn’t know who to blame. I tried to find somebody. I began to blame it on black people. I had to hate somebody. Hatin’ America is hard to do because you can’t see it to hate it. You gotta have somethin’ to look at to hate.”

He describes his thoughts about Ann back then; the woman who would end up becoming his best friend and giving his eulogy. “I will never forget some black lady I hated with a purple passion. Ann Atwater. Every time I’d go downtown, she’d be leadin’ a boycott.” In an NPR All Things Considered interview hosted by Melissa Block that they did together, Ann, when asked whether CP hated her, said, “Yes, he did, and I hated him just as hard as he hated me.” CP would describe himself as uneducated, and state that most members of the Klan were quite similar to him; poor, semi-literate, white-identifying men. This realization led CP to a powerful insight.

One evening, he and the Klan had been called upon to show up at a city council meeting in opposition to Ann’s group. They did, armed. “We would wind up just hollerin’ and fussin’ at each other.” “What happened? As a result of our fightin’ one another, the city council still had their way. They didn’t want to give up control to the blacks nor the Klan. They were usin’ us.” CP and Ann were elected co-chairs of a racial reconciliation meeting that included members of the community spanning from the NAACP to supremacists.

But their respective communities didn’t make it easy on them. “You’re sellin’ us out, Ellis, get out of my door. I don’t want to talk to you,” was how CP described his group’s response to him. “Ann was gettin’ the same response from blacks,” CP said. “‘What are you doin’ messin’ with that Klansman?’”

Still, together, Ann and CP would do the impossible; they’d bring their camps together. But doing so required something huge; they both had to learn to truly see the other, to see the beauty of humanity in one another. They’d each learn to look at the person in front of them, someone they’d been told was irreconcilably different, and see sameness, someone who was supposedly their opposite, and see themselves.

All three are examples of people who pooled their power and forged a better way forward. “It’s not right,” they all could rightfully have said, “But it’s okay. We’re gonna make it anyway.”

Now, imagine what changes when they, this new breed of Americans, ascend to power. Because they will.

Pauli Murray, African American, granddaughter of a slave and great-granddaughter of a slave owner, female, suffragist, activist (she was arrested for not giving up her seat – 15 years before Rosa Parks), gender nonconforming, LGBTQ+ and one of the most brilliant legal minds of the 20th century (Thurgood Marshall called her work the “bible of the Civil Rights movement”) had this to say about staying in the fight: “Don’t get mad, get smart.”

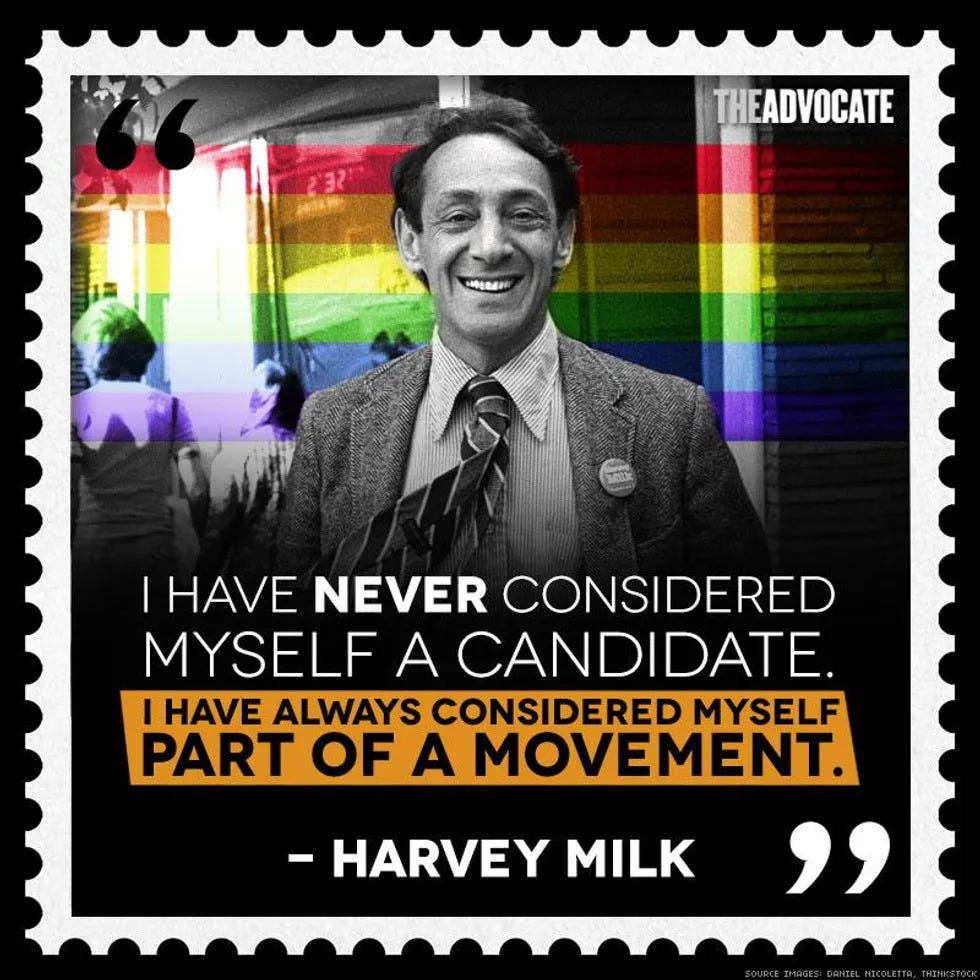

This is exactly the work that Bayard Rustin, Pauli’s friend and contemporary, mastermind behind almost every facet of the Civil Rights movement from the first Freedom Ride to its embracing of nonviolence to the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, and likely the first openly gay public figure in the United States (not to mention, my personal hero), was doing. Bayard was among the first to make the shift, as he described it, “from protest to politics”.

Arguing against the shortsightedness of factions, Bayard urged the Negro community to expand its vision and to build a working-class coalition that collaborated across racial lines for common economic goals, lobbying for a change in political strategy toward building and strengthening alliances with labor unions, Elks Lodges and the like, with churches, synagogues, mosques, and so forth.

And perhaps most importantly, he urged us to recognize the vote as the single most powerful lever of change in American society. He challenged us to not let one vote go uncast, using it to empower people who would, in turn, empower us and to enable those who’d been relegated to the margins to run. To work together as a collective to make wrong things right. That sounds suspiciously like what’s driving my sister Crystal and so many women. Bayard was right; both then and now.

This is how we win — by rejecting scapegoating, refusing to be splintered and shifting from protest to politics. We elect diversity-embracing people to every public office from the lowest on up in every state in the union. Every single one. We become judges and police officers, the people doing the hiring and writing the news. We recognize that our vote, given America’s unprecedented sociological shifting, is more powerful than ever and can only be “trumped” if we, the new majority allow it. And we accept that this perilous place we’re in is, at least partially on us for not seeing how the system was being gamed, and when we saw it, not believing it.

So, now, we fight like hell to make sure our voice is heard and our vote counted. We rescind every perverse law that undermines democracy and invalidates equality and we vow to never allow another election to be won because we didn’t (or couldn’t) show up. I want to end with a quote from Martin’s I Have a Dream speech delivered at the March on Washington that Bayard organized. But not the most famous section. I want to draw our attention to what he said before that; words that feel especially appropriate right now:

We have also come to this hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of Now. This is no time to engage in the luxury of cooling off or to take the tranquilizing drug of gradualism. Now is the time to make real the promises of democracy. Now is the time to lift our nation from the quicksands of racial injustice to the solid rock of brotherhood. Now is the time to make justice a reality for all of God's children.

He continued:

With this faith, we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope. With this faith, we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood. With this faith, we will be able to work together, to pray together, to struggle together, to go to jail together, to stand up for freedom together, knowing that we will be free one day.

And this will be the day – this will be the day when all of God's children will be able to sing with new meaning: My country 'tis of thee, sweet land of liberty, of thee I sing. Land where my fathers died, land of the Pilgrim's pride, from every mountainside, let freedom ring! And if America is to be a great nation, this must become true.

“It’s not right,” Whitney sang. “But it’s okay.” Because we’re gonna make it anyway.

It reminds me again that if we truly listen to one another (despite our differences), we might find commonalities and connection. I truly appreciate your work!

RD, I endorse your views. You imbue me with optimism, and it will take engagement and work.