There’s a Place for Us

How things like a century-old photo of two men in love also made me feel seen.

I can still remember it. I was sitting in my middle school American History class and came across a photo of a painting; JE Taylor's pictorial representation of the Battle of Bunker Hill; the one with Peter Salem firing his rifle at British Royal Marine officer Major Pitcairn. I remember staring at it, the first visual image I’d ever seen that included anyone other than people of obvious English ancestry in the events of our founding.

But what shocked me just as much was realizing that I held an assumption; one that I’d never thought to question. Somewhere along the way, I’d unconsciously embraced a devastating and disempowering false narrative; that brown-skinned people played no part in the Revolution; that we simply weren’t there. All my life, I’d had this feeling I couldn’t name, and that I didn’t know even had a name.

The feeling I’d been struggling with was displacement, and that picture was, for me, the beginning of addressing it, of writing diversity back into history. This process of re-finding my place in this story would prove to be multifaceted and ongoing. It’s what I experienced in college when I took the Myers Briggs Type Inventory, and discovered that I’m an INFP – introvert, intuitive, feeling, and perceiving.

It didn’t matter to me that in a society that values extroversion (outward focus), sensing (concreteness), thinking (facts) and judging (deciding quickly), that all four of my traits were “unpreferred” – especially for males – nor that only about 1% of the population shared my personality profile. I’d long known I was an outlier. But what the inventory gave me was a sense of belonging; even if INFPs were as few as they claimed, I was a type. There was a place for me.

I had a similar experience regarding handedness. Back in 2nd grade, I had a teacher who told me, the only left-hander in the class, that she didn’t know how to teach “someone like me” how to write. So, when adult me stumbled upon a whimsical novelty store at San Francisco’s Fisherman’s Wharf, I was surprised that things like left-handed scissors made me feel affirmed and validated in a way that, until that moment, I didn’t know I needed. As a result, to this day, I take the time to acknowledge fellow lefties; appreciating that our minds work differently.

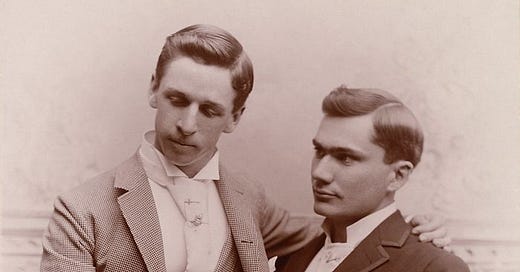

Then, there was the discovery of Hugh Nini and Neal Treadwell’s 2020 picture book, LOVING: A Photographic History of Men in Love 1850s-1950s. Hugh and Neal, both art collectors and spouses, came across a bargain bin photo at a flea market more than 20 years ago of two men who were clearly in love, but that, based on their attire, dated back to around the early 1900s – to a time when, the way we describe it today, same-sex relationships didn’t exist. Hugh and Neal would embark upon a twenty-year quest to collect as many of those photos as they could find wherever they could find them.

Their search resulted in a collection of over 2,800 photos, a massive cultural excavation that’s astonishing in its diversity (photos of 19th-century laborers and 20th-century professionals, cowboys and construction workers, artists and academics, soldiers and scientists, of all ages and ancestries) and in its breadth (spanning from the Civil War, through WW II, and into the 1950s).

The Loving photo book, like the painting of Peter Salem, impacted me profoundly; especially as someone who identifies as LGBTQ. Of course, it makes sense that we were there, doing our part to build our nation. Yet, we act as if gay people didn’t exist before Stonewall, and that if they did, they made no real contributions. But that’s clearly not true.

This was especially evident in the photo of two Negro servicemen in uniform, one resting his chin on the shoulder of the other. It challenged so many of our stereotypes, about gay African American men, about gay men in the military, and about gay men forming couple relationships long before coming out was a thing. Something about seeing them also made me feel seen.

Then, there was the small, quiet, yet profoundly revolutionary act by Iowa schoolteacher Jane Elliott. It was the evening of April 4, 1968 and it had just been publicly announced that Martin Luther King had been assassinated. Jane, stepping into that moment in the only way should could, decided that instead of just talking with her third-grade class about the prejudice that had led to Martin’s murder, she’d help them feel it – what it’s like to be told there’s no place for you.

“It’s a fact,” she told them the next day, after discussing Martin’s death and why it was such a sad thing, then explaining the exercise and getting into character. “Blue-eyed people are better than brown-eyed people.” And that was really all it took. “I watched what had been marvelous, cooperative, wonderful, thoughtful children turn into nasty, vicious, discriminating little third graders in a space of 15 minutes.”

In A Class Divided, the students, now adults, came together for a reunion. And each of them talked about how that one lesson changed their lives for the better, and that as tough as it was to go through, how grateful they were to walk, if only for an hour, in the shoes of the unpreferred. They got to learn how each of us, even through seemingly inconsequential actions like being kind or teaching our class empathy, help shape society itself. In the same way that Smokey the Bear taught us that only we can prevent forest fires, we also get to make Martin’s dream real.

That same day, while Jane was leading her children in the blue-eyed/brown-eyed exercise, the Supremes were in New York City performing a heart-rending version of Leonard Bernstein and Stephen Sondheim’s Somewhere (There’s a Place for Us), live on Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show, also in Martin’s honor.

The timeless lyrics of the song, written a decade earlier for West Side Story, paired with Diana’s reverent delivery, could not have been more moving. It evoked images of that same Promised Land Martin had spoken of just two nights prior in his sermon, when he shared of having been to the mountaintop. “There’s a place for us,” Diana sang:

Somewhere a place for us. Peace and quiet and open air, wait for us, somewhere. There's a time for us, someday a time for us. Time together with time to spare, time to learn, time to care; someday, somewhere. We'll find a new way of living; we'll find a way of forgiving, somewhere… There's a place for us, a time and place for us. Hold my hand and we're halfway there; hold my hand and I'll take you there – somehow, some day, somewhere.

“Yes, there's a place for each of us,” she said during the song’s interlude, with the other Supremes humming in the background. “And we must try to pursue this place, where love is like a passion that burns like a fire. Let our efforts be as determined as those of Dr. Martin Luther King, who had a dream that all God's children, black men, white men, Jews, Gentiles, Protestants, and Catholics, could join hands and sing that spiritual old hymn: ‘Free at last, great God, free at last.’”

In that moment, this overwhelmingly white-identifying audience, many, for the first time, began to learn what Jane Elliott’s third-grade class was also learning; how Martin’s death the night before was not just a loss for African Americans but for all Americans, how we’re all caught up together in this inescapable network of mutuality, and how the only way we create a place for any of us is by doing so for all of us.

It’s what I was learning at each step along the way, from the painting featuring dark-skinned Peter Salem and the Left-hander’s store to the Myers-Briggs and Nini and Treadwell’s book about men in love. Each was part of my own healing, affirming that there’s a place for me and empowering me to do the same for others.

And the Supremes? That better place they sang of, that dream that encompassed all of us was what was almost silenced on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel. But it wasn’t. Because we, the American people didn’t allow it to be. Collectively, we realized that if Martin was gone, then each of us had to join the chorus, taking up the song of the dream where he’d left off.

So, when those three women finished, when they’d sung their last “Somehow, someday, somewhere,” the audience took up the charge. Their resounding applause was deafening and the standing ovation instant.