Day 75: Why? (The King of Love is Dead)

Remembering Martin -- How Supremacists, by Taking Him From Us, Didn’t Break the Movement, or Kill the Dream. They Supercharged Them Both.

“So, I’m happy tonight – I’m not worried about anything. I’m not fearing any man! Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord!” Those were Martin’s final public words before doing his own version of a mic drop, walking away from the podium with absolute conviction. There was no wavering or equivocation on his part. He was fully ready to meet the moment. And he did.

Today is April 4, the anniversary of Martin Luther King’s death. But it’s so much more than that. Everything that happened beforehand prepared him for that moment, to infuse the movement with such resoluteness, knowing that what was to come was unstoppable. And all the progress that’s happened since has only proved him right.

“All we say to America,” Martin said earlier in that same sermon, “Is, be true to what you said on paper.”

If I lived in China, or even Russia, or any totalitarian country, maybe I could understand some of these illegal injunctions. Maybe I could understand the denial of certain basic First Amendment privileges because they haven’t committed themselves to that, over there. But, somewhere I read, of the freedom of assembly. Somewhere I read, of the freedom of speech. Somewhere I read, of the freedom of press. Somewhere I read, that the greatness of America is the right to protest for right. So, just as I say we aren’t gonna let any dogs or fire hoses turn us around, we aren’t gonna let any injunction turn us around! Well, I don’t know what will happen now. We’ve got some difficult days ahead. But it really doesn’t matter with me now...

And it didn’t. Because Martin knew that no matter what happened to him, this march toward the Promised Land was a done deal. In his mind’s eye, it had already happened. And no amount of government oppression or individual action could change that. Martin had already flipped to the end of the book. He knew how our shared story ends. And once we know that - we, like him, can say - “I’m not worried about anything. I’m not fearing any man.” On this day, it’s so important that we remember Martin, and what we lost when we lost him. But, if that’s all we do, we’ve left out part of the story – perhaps the most important part. We’ve missed what came after.

Today’s letter is a bit different, in that most of what follows is from the Conclusion of This Land Is Your Land. In it, I sought to not only capture the enormity of this fateful moment in American history, one that, for many of us, was almost unbearable – one blow too many – but, to also show how it was supremacy, not an assassin’s bullet, that took Martin from us. But, even that’s not all. I wanted to reveal the truth Martin already understood; that supremacy had no future. He’d seen the Promised Land of a “For All” America. And nothing they could do could stop it.

“I have a dream today.”

That’s where things started back with Martin’s watershed speech on the Washington mall on a hot D.C. August day. It was a time of unprecedented change for African Americans and for the nation. Never before had there been such a gathering at the capital. Bull Connor’s police dogs and fire hoses, and the arrests that precipitated the famous Letter from Birmingham Jail had just happened in May. In three short months, they’d gone from jail cells to the Lincoln Memorial, from fighting to get people to pay attention to being all anyone was talking about, from invisible to unstoppable. Before, the singing of “I ain’t gonna let nobody turn me around” was faith. Now it was fact.

People had doubted that they would come, but come they had; by the thousands, from every place across the nation; on buses, planes, trains and in cars, hitchhiking and carpooling and every other way possible. They came together in solidarity, in hope and in power, and the world watched. This was a time of upheaval, unrest and uncertainty. The tectonic plates of our nation were shifting and, collectively, we were headed somewhere we’d never gone before; a people buoyant with hope and rising to new heights on the power of a dream.

Then, the killings began in earnest. Addie Mae Collins (age 14), Cynthia Wesley (14), Carole Robertson (14), and Carol Denise McNair (11) – all killed in Birmingham’s Sixteenth Street Baptist Church bombing. President John F. Kennedy assassinated in Dallas. Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner murdered in Mississippi, and so many others. And Martin? Less than five years after inspiring the world with his dream, he would join them.

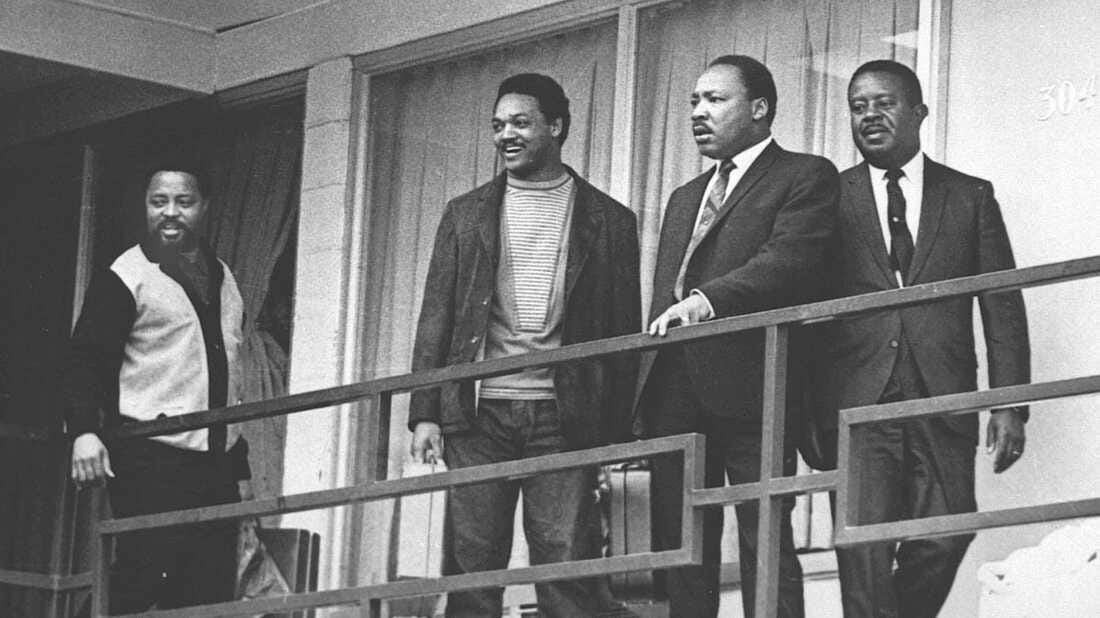

Martin’s death, followed almost immediately by Bobby Kennedy’s, would inspire multiple tributes, including Abraham, Martin and John, written by Dick Holler and recorded by Dion; which recognized the deep love of America that these men held in common, and the price they’d pay for holding it. The fateful shot on April 4, 1968, that felled Martin as he stood on the balcony of Memphis’ Lorraine Motel would be devastating; not only taking his life but gravely injuring a movement. That movement, however, had already been languishing months before.

People were growing increasingly doubtful that their many sacrifices had made any difference and discouraged that their lives were no better years after the passage of those historic civil rights acts than they’d been before them. They were also dealing with a significant degree of backlash; where the in-power group punishes the oppressed group for every step of progress (whether material or symbolic) toward parity that they take. As a result, life for the majority of African Americans was effectively worse.

As such by 1967, Martin was being ridiculed and vilified by the very people he’d galvanized. Many, even in his own organization, simply couldn’t follow the train of thought that led him from Negro rights to protesting the Vietnam War to confronting poverty on behalf of all people in the world; not just the American Negro. For Martin, however, there was an unwavering through-line, clearly and resolutely based on what he declared America’s Three Great Evils; the evil of racism, the evil of poverty, and the evil of war. He was absolutely convinced that a “For All” society was the only viable society.

In a May 10, 1967 address, a month after his Riverside Church speech, he would state:

There can be no gainsaying of the fact that racism is still alive all over America. Racial injustice is still the Negro’s burden and America’s shame. And we must face the hard fact that many Americans would like to have a nation which is a democracy for white Americans but simultaneously a dictatorship over black Americans. Now there are those who are trying to say now that the civil rights movement is dead. I submit to you that it is more alive today than ever before. What they fail to realize is that we are now in a transition period. We are moving into a new phase of the struggle.

For well now twelve years, the struggle was basically a struggle to end legal segregation. In a sense, it was a struggle for decency. We will not forget the Freedom Rides of sixty one, and the Birmingham Movement of sixty three, a movement which literally subpoenaed the conscience of a large segment of the nation to appear before the judgement seat of morality on the whole question of civil rights. We will not forget Selma, when by the thousands we marched from that city to Montgomery to dramatize the fact that Negroes did not have the right to vote. These were marvelous movements. But that period is over now.

The new phase is a struggle for genuine equality… on all levels, and this will be a much more difficult struggle. You see, the gains in the first period, or the first era of struggle, were obtained from the power structure at bargain rates; it didn’t cost the nation anything to integrate lunch counters. It didn’t cost the nation anything to integrate hotels and motels. It didn’t cost the nation a penny to guarantee the right to vote. Now we are in a period where it will cost the nation billions of dollars to get rid of poverty, to get rid of slums, to make quality integrated education a reality. This is where we are now.

Despite doubts about Martin’s new direction, the idea of a future without him was something that hadn’t even been imagined. But suddenly he was gone. In the aftermath, with a devastated people overcome with grief, many concluded that it was all over. “The dream might still be alive somewhere,” they said, “But the movement – the movement died at 7:05 pm on a gurney at Memphis’ St. Joseph hospital.” And it almost was. Almost.

In a live performance of what’s been called “the saddest song ever written”, Nina Simone spoke sorrowfully of what had been lost.

The song, Why? (The King of Love is Dead), written by her bassist, Gene Taylor, on the night Martin was killed, immortalized not just his life, but his place at the heart of what made America good:

Once upon this planet Earth, lived a man of noble birth; preaching love and freedom for his fellow man. He was dreaming of the day, peace would come on earth to stay; and he spread his message all across the land.

“Turn the other cheek”, he’d plead, “Love thy neighbor” was his creed. Pain, humiliation and death, he did not dread. Yes, with his Bible at his side, from his foes he would not hide: It’s hard to think that this great man is dead.

He had seen the mountaintop, and he knew he could not stop; always living with the threat of death ahead. Your parents - they’d better stop and think, ‘cause we’re heading for the brink, now – you’d better believe it. What’s gonna happen now that the King of love is dead?

Will, will the murders never cease? Are they men or are they beasts? What do people, what do they think they have to gain? Well, will your nation stand or fall? Is it too late for us all? And did Martin Luther King just die in vain?

You know, that he was for equality, for all people, you and me. Full of love and good will; hate was not his way. He was not a violent man, so, tell me honey, tell me if you can, just why was he shot down the other day?

It was prejudice, it was hate; bigotry sealed his fate. Go on, cry, cry – your tears won't change a thing. Will my country ever learn? Must it kill at every turn? We’ve got to know by now what the consequences will bring.

Yes, he had seen the mountaintop, and he knew he could not stop; always living with the threat of death ahead. Folk, you’d better stop and think, for we’re all heading for the brink – hear me now! What will happen now?

What’s gonna happen, now… that the King of love is dead?

Over time, we’d come to appreciate Martin’s unyielding, unshakable faith in his fellow Americans, and together, who we could be. His own journey had formed him into a man utterly convinced that given the chance, all of us could live as our best selves and that if we did, the world itself would change. He believed in the inherent goodness of people; including white-identifying people, and not just the ones sympathetic to the Negro cause.

The black community knew that Dr. King loved his “white brothers” and appreciated that he did; especially when they could not reach as far. So, for grieving African Americans, it was a powerful statement that the only man telling them to “love white people” was the one they killed. But that’s also the irony of supremacy; the more we buy into it, the less of a future we have. The same movement the assassins sought to eradicate; the torch they hoped to snuff out would, in its dying, erupt into a nationwide wildfire; searing consciences and sparking emboldened action everywhere.

The very public execution of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. would set off riots in more than 100 American cities. Nothing like it had been seen before, nor since, that is, until 2020; our summer of reckoning. By killing him, they all but ensured the coming of the same “new phase of the struggle” Martin had foretold. The movement didn’t die. It evolved. It evolved into the words of Senator Robert Kennedy, who, on the night of Martin’s passing, said:

Martin Luther King dedicated his life to love and to justice for his fellow human beings, and he died because of that effort. In this difficult day, in this difficult time for the United States, it is perhaps well to ask what kind of a nation we are and what direction we want to move in. For those of you who are black and are tempted to be filled with hatred and distrust at the injustice of such an act, against all white people, I can only say that I feel in my own heart the same kind of feeling. I had a member of my family killed, but he was killed by a white man. But we have to make an effort in the United States, we have to make an effort to understand, to go beyond these rather difficult times.

It evolved into nonprofits and charities working on social justice from every angle imaginable; from Head Start and early childhood education, to economic empowerment to women’s and LGBTQ+ rights, to unionization, to voter registration, to environmental consciousness, and so much more. It evolved into minority empowerment groups like the Asian American Political Alliance, and the vast proliferation of activism and advocacy groups that were part of the nationwide Rainbow Coalition, and into the groundswell of support that almost certainly would have taken Robert Kennedy to the White House had he himself not been assassinated.

It evolved into the diversification of politics, including Shirley Chisholm and Barbara Jordan, the first African American Congresswomen. Rep. Chisholm was further distinguished as the first African American presidential candidate, whereas Rep. Jordan broke all kinds of barriers as African American, female, and LGBTQ+ (from Texas, no less).

Andrew Jackson (Atlanta) and Richard Arrington (Birmingham) each became the first African American mayors of those southern cities. Norman Mineta became the first Asian American mayor of San Jose and Ben Nighthorse Campbell became Colorado’s first Native American US Senator. Then came Sonia Sotomayor, our nation’s first Latinx American US Supreme Court Justice, followed by Ketanji Brown Jackson, the first female African American to sit on “the highest court in the land.”

This movement of diversity and equality, like wildfire, further sprang forth as everything from blind piano players to one-armed drummers, from humanity-advancing activists to democracy-defending journalists, from female Green Berets to neurodiverse scientists. Then, there was the explosion of firsts: the first Native American astronaut to fly into space (John Harrington), the first African American comic book superhero (Sam Wilson, the Falcon – also, incidentally, the new Captain America!), the first Asian American (Akiko Wakabayashi) and African American (Trina Parks) Bond Girls.

There was the first minority US Navy Master Diver (Carl Brashear), the first openly transgendered person to be elected to state legislature (Althea Garrison), the first African American head of a historically white religious denomination (Rev. Bill Sinkford, 7th President of the Unitarian Universalist Association), and a young, unknown African American woman hosting a half-hour morning talk show, AM Chicago; at the time, last place in the ratings.

After taking the show to first place in a matter of months, she would go on to launch her own syndicated talk show, and become the biggest name in television, as well as one of the most trusted and admired people in the world. By 2004, Oprah Winfrey would be the world’s only African American billionaire, and starting in 2006, she would put all that she had to work on behalf of a relatively unknown, but electrifying presidential candidate, freshman US Senator, Barack Obama.

Her influence was so powerful that immediately after her endorsement, Time magazine’s October 23, 2006 cover featured Senator Obama with the caption "Why Barack Obama could be the next president." Though, at the time, the idea was as far-fetched as “Why there could be life on Mars”, we nevertheless know the story from there. The 2008 Obama for America campaign would be supported by the same diverse, broad-based network that Martin’s death, forty years prior, had galvanized. Never had a campaign had such vast reach, across all of America.

And that movement still lives. Efforts to combat Martin’s three great evils are everywhere, manifesting as everything from the interlinked arms of “walls of moms”, “walls of veterans,” and “walls of clergy,” people from all walks of life who, in the summer of 2020, placed their bodies between the troops and the protestors seeking to elevate our conscience, to Portland, Oregon’s Street Medicine, which takes medical care directly to the unhoused.

It lives in projects like Youth v. Gov., the Netflix film about the 21 incredibly diverse American youth who are suing the US government for willful climate inaction and who hope to stabilize the global climate system by 2100, and in Run for Something, which empowers everyday Americans to pursue a turn in political office. And, as we know, it lives on in Generation Alpha, the first minority-majority, non-racialized, non-genderized, non-heteronormative, non-religionized, fully diversity-embracing birth cohort in human history.

In every city, town, county and state, there are people carrying the torch, helping us become a nation where each of us cares for all of us. But even that’s understating the breadth and depth of the movement. This migration away from social dominance ideology stems all the way back to those who did what it took to abolish slavery itself. Then, a century later, it was the energetic force behind the Civil Rights era in all its permutations. And likewise, it’s what’s stirring within us today as we approach this new threshold, this sea change, this great sociological shift.

Today, we owe so much of who we’re becoming, an incalculable debt, really, to those who came before us, who bore on their backs the spiritual wounds of a nation. It was they who showed us how to simultaneously cleave to the promise of America while hating its abuses, how to love its heart while rejecting its ruthlessness, how to throw off the yolk of oppression without becoming the new oppressors.

It was they, our spiritual forebears, who would teach us how to fight fiercely, fearlessly and relentlessly for justice without sacrificing our humanity. And in the ways they lived and even died, they’d bequeath us hope and, like the Hollow Coves sang, remind us that there are indeed blessings all around us, if only we can open our eyes. This lesson was always important, but today, given how we’re changing, and the immense trials we’re facing, it’s the key to our survival.

The truth of it is that our situation is dire. We’re a society suffering from wounds to the soul that, if left untreated, could very well be the end of us. But it doesn’t have to be. The end. If we so choose, we can, like Oprah once said, turn our wounds into wisdom. We can jettison any construct that hinders our humanity, and embrace ones that foster Beloved Community. We can replace every system built on supremacy with true democracy – a society that works for every one of us. And we can embrace our own diversity, our particular genius, and use it to help build an enduring future for all of us.

While it might not be obvious, we’re living in an unprecedented time, one where the tectonic plates of our nation, if not the world, really are, once again, shifting. Each day, the societies we have, grow increasingly incompatible with the people we’re becoming. And as scary as that might feel, it’s not really a bad thing. Because everybody’s changing, it was always a necessity that we endow our societies with the ability to change with us. There’s something quite remarkable about the fact that each of us, simply by living our lives, gets to shape our collective fate. And here, in this grand story, we’re so much more than just the beneficiaries of those who came before us; we get to be benefactors to those who come after.

This spiritual unfolding is, in essence, how the inescapable network of mutuality and the single garment of destiny work. All of which, of course, leads us back to Martin. America needed someone to be its ethical Moses, and Martin, perhaps more than anyone in our history, would shoulder that burden. He would take it upon himself to help a nation find its way out of the wilderness of advantagism and toward the Promised Land, a Beloved Community where everyone thrives and we all belong – a land made for you and me.

But it wasn’t about him being a miracle worker. His greatest feat was convincing so many of us that we, ordinary people, could perform miracles. And we would; blessing the loaves of humanity and, in the process, nourishing a nation. This ability to inspire within us a belief in what’s possible would, with his passing, be our nation’s most profound loss.

Which is probably why we gravitate so strongly toward the ending of his I Have a Dream speech. And rightfully so. But before getting there, Martin, there, in front of the Lincoln Memorial, expressed other words that we sorely need to hear; including some that sounded a lot more like President Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, and that resonated with the themes of President Kennedy’s Civil Rights Address given that same summer:

We have also come to this hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of Now. This is no time to engage in the luxury of cooling off or to take the tranquilizing drug of gradualism. Now is the time to make real the promises of democracy. Now is the time to lift our nation from the quicksands of racial injustice to the solid rock of brotherhood. Now is the time to make justice a reality for all of God's children.

He would continue, in words that could just as easily describe the plight of the majority of Americans today as they did that of African Americans in 1963:

It would be fatal for the nation to overlook the urgency of the moment. This sweltering summer of the Negro's legitimate discontent will not pass until there is an invigorating autumn of freedom and equality. 1963 is not an end, but a beginning. Those who hope that the Negro needed to blow off steam and will now be content will have a rude awakening if the nation returns to business as usual. There will be neither rest nor tranquility in America until the Negro is granted his citizenship rights. The whirlwinds of revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our nation until the bright day of justice emerges.

Though the Avett Brothers, in We Americans, phrased their confession as an individual one, the truth of it is for all of us. We’re all sons – and daughters – of both God and man, living in a land that we dearly love and that breaks our hearts. It’s the same sentiment reflected by James Baldwin in Baldwin’s Nigger, where he acknowledges that, despite denials and displacement, he is, in every way, an American; that his school really was the streets of New York and his frame of reference, the likes of George Washington and John Wayne. And in this realization, we find that same combination of love and heartbreak:

What is happening in this country... is that brother has murdered brother, knowing it was his brother. White men have lynched Negroes, knowing them to be their sons. White women have had Negroes burned, knowing them to be their lovers. It is not a racial problem. It’s a problem of whether or not you’re willing to look at your life and be responsible for it and then begin to change it.

That great Western House I came from is one house, and I am one of the children of that house. Simply, I am the most despised child of that house. The American People are unable to face the fact that I am flesh of their flesh, bone of their bone, created by them. My blood, my father’s blood is in that soil.

The alternative to an America that’s true to the virtues that birthed it, is and has always been, a harsher, harder and more disconsolate land; one where lives of beauty and diversity are never allowed to flower, and where we take what we want, with no regard for what it costs us. Where the land of opportunity becomes the land of opportunism, where those tasked to serve society find themselves increasingly betraying their calling, and where the hope that once burned like the summer sun no longer even breaks the horizon. That’s one future. But it doesn’t have to be ours. Martin knew this, which is why he presented another path, articulated as a dream:

And so, even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream. I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.’ I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia, the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.

I have a dream that one day, even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice, sweltering with the heat of oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice. I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. I have a dream today!

With this faith, we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope. With this faith, we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood. With this faith, we will be able to work together, to pray together, to struggle together, to go to jail together, to stand up for freedom together, knowing that we will be free one day.

And this will be the day – this will be the day when all of God's children will be able to sing with new meaning: My country 'tis of thee, sweet land of liberty, of thee I sing. Land where my fathers died, land of the Pilgrim's pride, from every mountainside, let freedom ring! And if America is to be a great nation, this must become true.

This dream, one that threads through every facet of our nation’s history and that is suffused into our marrow, is, and has been, long before it was articulated by Martin, our guidepost, our best destiny, our Zion. And despite the toils and snares, the struggles and setbacks, this place we’re at now, this diverse blossoming of America, was always our trajectory. Through it all, we’ve continued to reify the yearning that birthed us and the hope that held us fast. It’s what stirs so powerfully within us each time we sing, Oh, deep in my heart, I do believe, that we shall overcome someday.

The depth of resolve captured in those words, if we allow it, resonates within us, like a vibration in our bones. And that, this deep and resolute knowing, brings us back to that moment we touched on in the beginning; to the last public words Martin would ever speak, and to how those words still resonate, now, more forcefully than ever:

We’ve got some difficult days ahead. But it doesn’t matter with me now. Because I’ve been to the mountaintop. And I don’t mind. Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will. And He’s allowed me to go up to the mount. And I’ve looked over. And I’ve seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land.

As much as America has forever been defined by a common dream, it’s this vision of the Promised Land it evokes that’s guided us, leading us forward. It is, in and of itself, a sacred covenant; an enduring hope that we will get there; as long as we endeavor to do so as one; as a diverse, yet united people, committed to enacting democracy, as each of us, in our own way, advances humanity. It’s how we hold hope high and keep the faith, honor our past and craft for ourselves a future. It’s how, together, we’re able to make this long-held dream, finally, a reality.

“I come as one,” Oprah once said, quoting Maya Angelou, “But I stand as 10,000.” Now, more than ever, we need the lessons people like Martin, Bayard, Rosa, Amelia, and so many others on whose shoulders we stand sought to teach us. And if we can breathe those lessons in, like the scent of fresh bread or the world after the rain, we’ll finally understand what they understood – this can’t be stopped.

Today is April 4, day 75 under this administration. We have just 581 days until the 2026 elections, 1,312 days until the 2028 elections, and 1,380 days until Martin’s 100th birthday. So, when do we fight? Today, tomorrow, and every day between now and then. Where do we fight? Anywhere and everywhere we see injustice occurring or oppression increasing. And, how do we fight? In every way we can.

The song I have for you today is We Shall Overcome. The video concludes with Pete Seeger, one of my personal heroes, singing the song he brought to the movement. But instead of just listening to it, I wanted you to also hear what Martin himself had to say about it. The recording is an excerpt from a sermon Martin gave at the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C., on March 31st, 1968, just four days before his death. It’s exactly the message we need to hear today.