1964 - 2024: Meeting History

Election Reflections #8: What the Last 60 Years Have to Teach Us About the Present We're Living and the Future We're Choosing (+ Reflections On My 60th).

Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced. – James Baldwin

“I Can’t Believe It’s Not Racism!”

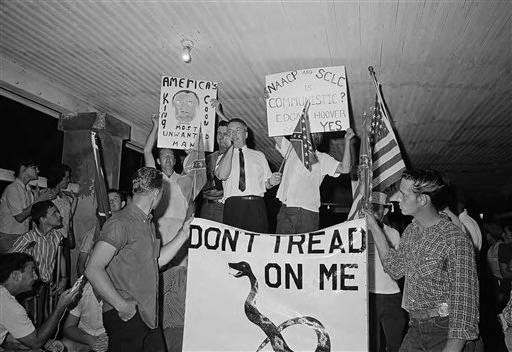

What do you do when there are photos of uniformed police officers and firefighters brutally attacking children? You take Goebbels’ advice and rewrite the narrative. You concoct a Really Big Lie – the kind that can convince people that squares are circles. (“Gee, Fred, I know these new-style tires are supposed to be great,” says Barney Rubble to his best bud Fred Flintstone, teeth chattering as they bump along on square tires, “But don’t you think they ride kind of rough?”)

You start out in 1954 by saying, ‘Nigger, nigger, nigger’. By 1968 you can't say ‘nigger’ – that hurts you. Backfires. So you say stuff like forced busing, states' rights and all that stuff. You're getting so abstract now [that] you're talking about cutting taxes, and all these things you're talking about are totally economic things and a byproduct of them is [that] blacks get hurt worse than whites. And subconsciously maybe that is part of it. I'm not saying that.

But I'm saying that if it is getting that abstract, and that coded, that we are doing away with the racial problem one way or the other. You follow me – because obviously sitting around saying, ‘We want to cut this,’ is much more abstract than even the busing thing, and a hell of a lot more abstract than ‘Nigger, nigger’.” – Lee Atwater, the New York Times October 6, 2005

In the above quote, originally part of an anonymous interview given in 1981 while serving as a member of the Reagan administration, New Right political strategist Lee Atwater summed up his group’s strategy — a gradual progression from gross offenses like slavery to increasingly more rarefied forms of discrimination like coded language.

He was referencing 1954 because that’s the year of the US Supreme Court’s unanimous Brown v. Board of Education decision, which made segregation illegal. But the ideology that drove Jim Crow and racism, which created separate drinking fountains and led to church bombings didn’t disappear. It simply changed its clothes.

In the vacuum caused by the SCOTUS ruling, there emerged another set of policies that were just as debilitating, but due to their amorphous, covert and embedded nature, far more difficult to identify. Toxic framing, from “states’ rights” to “forced bussing”, from criminal background checks to “religious freedom” allowed a kind of depersonalized discrimination to be uploaded, like malicious code, right into our societal mainframes.

“If it is getting that abstract, and that coded,” Atwater said, “We are doing away with the racial problem one way or the other.” But they weren’t “doing away with the racial problem”. They were doing away with being held accountable for the problems they, themselves were causing. Big difference. So, instead of enacting laws that overtly discriminated, or that trumpeted segregation as their intent, the very facets of society that keep it functioning were themselves hacked; altered on a molecular level.

The result was a kind of Machiavellian genius; warping our societal infrastructure to consistently produce preferential, discriminatory outcomes. But even worse, they accomplished this while wrapping themselves in the American values of impartiality, equality and fairness, not unlike how self-described “patriots” have recently taken to replacing the flying of the Confederate flag with the American flag, often hoisted in the beds of their trucks outfitted with gun racks. Which, of course, sends a message – the flag belongs only to us.

The whole thing reminds me of those '70s I Can’t Believe It’s Not Butter commercials. But, in my mind, the woman in pearls is saying, “Looks like racism. Tastes like racism. I can’t believe it’s not racism!” “All the flavor,” I can hear the male announcer saying, “None of the guilt!” This strategy allowed them to stave off the inevitable for a decade after the Brown decision. Then, all of a sudden, it was as if the nation caught fire.

Right from the beginning, 1964 was a year of crisis. President Kennedy had just been assassinated the November prior, and just before that, the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom and the Birmingham Campaign. Freedom Summer was in full swing and the Civil Rights Bill of 1964 was working its way through Congress.

As we saw in Three Truths (And a Really Big Lie), the occasion that would lead to Malcolm and Martin meeting for the first and only time would be their joint attendance at the Senate hearings in Washington DC. Much of the heat contained in Malcolm’s Ballot or the Bullet speech was aimed squarely at the large contingent of Democrats fighting against the Act’s passage.

That was also the year Strom Thurmond, former presidential candidate, avowed segregationist and conductor of the longest filibuster ever by a lone senator – 24 hours and 18 minutes nonstop to prevent the passage of an already severely compromised 1957 Civil Rights Act, left the Democratic Party for good, for a new Promised Land – the Republican Party. This was actually the second time Strom had left. The first time was to helm a new political party officially known as the States’ Rights Democratic Party, but far better known by its nickname – the Dixiecrats.

Though they declared themselves for states’ rights, what that really was, was code for what they were actually for – segregation. They believed that the federal government could not pass laws requiring that they treat all Americans equally. This occurred in 1948 in a race where incumbent Democrat Harry Truman was the victor. For that election, Strom was put forth on a third-party ticket where he and running mate Fielding Wright would go on to win four states – Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana and South Carolina. Their platform, adopted at their Oklahoma City convention stated:

We stand for the segregation of the races and the racial integrity of each race; the constitutional right to choose one's associates; to accept private employment without governmental interference, and to earn one's living in any lawful way. We oppose the elimination of segregation, the repeal of miscegenation statutes, the control of private employment by Federal bureaucrats called for by the misnamed civil rights program. We favor home-rule, local self-government and a minimum interference with individual rights.

By the 1952 Democratic convention, the States’ Rights Democratic Party was essentially dissolved with the former Dixiecrats, after signing a loyalty pledge, integrated once again into the party. Twelve years later, just after the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, Strom, stating that the Democratic Party no longer represented “people like him,” left for good.

That was the beginning of a mass defection of politicians who could trace their Democratic lineage back to its founding in 1828, the segregationist takeover of the Republican Party, and the “Solid South’s” shift from a history of only backing Democrats to supporting new-style Republicans whose values reflected the Dixiecrat platform and who, in their minds, represented “people like them”.

This was also the beginning of what would emerge as the New Right; an effort that required the politicization and recruiting of churchgoing Americans across the nation, and that would change everything about American politics. By the mid-’70s, a new plan had been formulated, one that, over time, would set them on a course to sidestep democracy and bring both Congress (which had passed the 1964 Civil Rights Act) and the Supreme Court (which had unanimously ruled on Brown v. Board) to heel, starting with the 1980 presidential election and the deals made with Republican Ronald Reagan. But none of that would be possible without the takeover of key social institutions, from the SBC to the NRA and the GOP itself.

How We Got Here

Founded in 1854, the Republican Party (also historically called the “Grand Old Party” or GOP), is the second oldest currently existing political party, behind the Democratic Party. Ironically, the impetus for its formation was to combat the extension of slavery into the territories and to promote more vigorous modernization of the economy.

While a young GOP had virtually no presence in the South, Democrats, within a few years, had enlisted the pro-slavery faction of the now-defunct Whig party, as well as members of other smaller splinter groups, giving them majorities in nearly every Northern state.

In 1860, however, various issues, including slavery’s potential expansion into the territories, split the Democrats into factions. Lincoln, prevailing in the North, and with electoral votes distributed between candidates in the South, won, with virtually no support from pro-slavery Democrats.

Even before his inauguration, seven Southern states declared their secession and formed what became known as the Confederacy with four others joining later. Lincoln’s success in guiding the Union to victory and abolishing slavery established the GOP’s political dominance for the next 75 years.

Comprised of northern Protestants, corporate leaders, professionals, factory workers, farmers, and newly vote-eligible coloreds, the party was pro-business, banks, railroads and civil rights. It supported factory worker protections and, under Theodore Roosevelt, adopted greater focus on foreign policy, including immigration.

The GOP nevertheless lost its majorities during the Great Depression, and the Democrats under Franklin D. Roosevelt formed the “New Deal” coalition; which greatly expanded their banner to include labor unions, European ethnics, and a good number of African Americans.

This coalition enabled FDR to be elected four times and for the Democrats to maintain political dominance until 1968, with a win by Republican Richard Nixon, after LBJ, signer of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, had opted not to run a second time and Bobby Kennedy, the other front-runner, had been assassinated.

Though the Democratic Party’s uneasy alliance of pro- and anti-segregationists would ultimately shatter with Johnson’s singing of the Civil Rights Act, the cracks were evident much earlier; spanning back to FDR’s death in 1945; three months into his fourth term. Three years later, led by President Harry Truman, who took over office after Roosevelt’s death, Democrats adopted their first real civil rights plank, which infuriated the party’s segregationist faction.

Then, two weeks later, Truman signed Executive Order 9981; thereby officially integrating the nation’s armed forces. And for that same segregationist faction, that was a last straw. They walked out, formed the aforementioned Dixiecrats and nominated Strom as their rival presidential candidate.

Though, a few years later, they’d begrudgingly return to the Democratic Party, they’d do so more ensconced in their ideology than ever, vowing to continue fighting for their version of America from the inside, brandishing their power like a weapon throughout much of the sixties, and resorting to increasingly hateful language and escalating acts of violence.

It was actions like those of JB Stoner and hearing Dixiecrats, as they fought against the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights bill, say things like, “We will resist to the bitter end any measure or any movement which would have a tendency to bring about social equality” that no doubt led a disgusted Malcolm to frame the issue in similar stark terms – the ballot or the bullet.

That same year, 1964, Republican Barry Goldwater mounted an unsuccessful bid for the Presidency; winning only his home state of Arizona and five states in the Deep South; none of which had ever voted Republican before. Their contrarian votes were primarily intended as an act of protest against the Civil Rights Act passed by their own party; even though a majority of Republicans in Congress also voted in favor of it. Still, segregationists saw the Republican Party, by that time, as the lesser of two evils.

And that’s the irony of it; the GOP’s longstanding commitment to civil rights is part of what made it vulnerable to a hostile takeover. Because with the segregation issue now off the table, supremacists were no longer reticent to migrate to the party; especially with so many African Americans now registering as Democrats.

Nixon strategist Kevin Phillips, in a 1970 New York Times interview, described how the leaders of the newly taken-over party had purposefully abdicated the African American vote. The assumption was that going forward, they’d never get more than 10 - 20% of the "Negro vote and they don't need any more than that," he said, describing a tactic that simply can’t continue to work in the society we’re becoming.

"The more Negroes who register as Democrats in the South,” he continued, “The sooner the Negrophobe whites will quit the Democrats and become Republicans. That's where the votes are; without that prodding from the blacks, the whites will backslide into their old comfortable arrangement with the local Democrats." And because of efforts like the one Kevin described, southern states that had been loyal to the Democratic Party for 150 years would completely jump ship in another 20.

When you think about it, this whole story is almost unimaginable. The party that came into existence to end slavery would become the home of supremacists, whereas the party that built not just slavery itself, but Black Codes and Jim Crow, that staged lynchings and murdered civil rights activists would be the one through which our first African American president would rise. But I also don’t believe this is the end for the GOP. Or, at least it doesn’t have to be. I still hold out hope that our better selves will win out.

A Measure of Indomitable Goodness

I shared in Three Truths (And a Really Big Lie) how my grandmother Mary could acknowledge Democrat George Wallace’s startling turn of behavior and still inexplicably (to me, anyway) recognize that there was more to him than that. She believed that while he wasn’t, at that moment, being guided by his conscience, it was still there, because, according to her, God put it there. We can harden our hearts and lose our way, she’d explained to me, and those actions might hide who we really are – even from ourselves. At least for a while. But it never lasts. I’d discover she was right.

George, after being mortally wounded in a shooting while on the presidential campaign trail, not only recanted his previous segregationist stance but began genuinely apologizing to all those he’d hurt or caused to be hurt. He started with personal apologies to a long list of civil rights leaders, before expanding to include appearances in historically black churches all over the state, where he apologized and asked for forgiveness.

He kept at it, seeking to make amends in the ways he knew how, and in a move that says just as much about the hearts of African American Alabamians as it does about George himself, the former forgave the latter. Unbelievably, George, in 1982, won the governorship with more than 90% of the African American vote. But that’s not all. George, for his part, would go on to appoint a record number of African Americans to state positions, including two cabinet members, just one example of his lifelong commitment to undoing some of the damage he’d done.

Something similar happened with Strom Thurmond, in my mind, the most ardent segregationist of his time. In 1971, he’d add one of the first African Americans to a Senate staff and, in 1983, he’d be among the first to voice support for legislation to make Martin Luther King’s birthday a federal holiday. Then, upon his death, Strom’s first-born child, a daughter, Essie Mae Washington-Williams, born to an African American mother, came forward.

Turns out her mother was Strom’s first love, and though society came between them, Strom made it a point throughout Essie Mae’s life to be a dad to her, giving her, at all times, open-door access to him and financially providing for her. As a father should. After she’d come forward, the Thurmond family publicly acknowledged her parentage and added her name to a monument to Strom on the statehouse grounds.

But this revelation wasn’t a surprise to friends, staff members and South Carolina residents who, based on Strom’s ongoing interest in her and the way he’d walk out of meetings if she needed him, not to mention, the resemblance, had long figured out that she was his child. Essie later applied for membership into both the Daughters of the American Revolution and the United Daughters of the Confederacy, as was her due.

Then, there are people like 72-year-old ex-Klansman Elwin Wilson. "You made a vow,” said a younger man during one of the many harassing phone calls Elwin had received, “Before God and your white brothers. How could you go against that?"

What had he done to warrant this kind of treatment? He’d apologized, publicly, to Congressman John Lewis for being part of the group that beat him and then-55-year-old Albert Bigelow, John’s Anglo Freedom Rider travel companion nearly 50 years prior. That’s it. He was marked a traitor because he regretted assaulting someone. Elwin was 22 when the incident occurred, John, 21.

“He started crying, his son started crying, and I started crying,” was how John Lewis later described the meeting where Elwin and his adult son traveled to DC so Elwin could apologize in person. The two men, forming a formidable friendship, would go on to make a number of public appearances together over the next two years, including a heavily viewed Oprah Winfrey Show, as well as being jointly presented with awards from groups committed to fostering the kind of healing evidenced by John and Elwin’s relationship.

Elwin, when asked about the calls he was getting during a CNN interview he and John did together, said, in his thick southern drawl: “Well, my daddy always told me that a fool never changes his mind and a smart man changes his mind. And that’s what I’ve done and I’m not ashamed of it. I’m not trying to be a Martin Luther King or something like that,” he added. “I never would have thought I could apologize to this many people. I feel like I’m apologizing to the world right now.”

Regarding his ability to forgive Elwin and others who’d behaved similarly, John would say, “It’s in keeping with the philosophy of nonviolence. That’s what the movement was always about,” he’d conclude, “To have the capacity to forgive and move toward reconciliation.” When Elwin died four years later, John was among those who eulogized him.

As I reflected on this unlikely friendship between these two men, I felt like I was right back there in our old living room, a mile west of downtown Birmingham, with Mary explaining how a measure of indomitable goodness lives in the heart of each of us; tucked away in the warmth of our bosom, like a planted seed shielded from the harsh light of our worst deeds. As a result, even today, this is how I endeavor to view others. It’s part of how I keep her alive.

George, Strom and Elwin are all examples of how it’s possible to do so much more than look like we’re leaving racism and bigotry behind. We can actually do so. They remind me that it’s the truth of who we are at our core that wins out in the end. I can’t help but believe this also holds for the party that came into existence to end slavery and that spent more than a century working to advance equality.

We’ll Rise Up

As for me, today, on my 60th birthday, I’m especially aware of what an honor it is to have lived through this amazing juncture of our shared story. I think about the time from then to now, from 1964 to 2024, and I can’t help but feel our nation’s history flowing through my veins.

It’s strange being born at such a consequential time and place, sandwiched between the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act, in a southern town struggling mightily with the sins of segregation, but also to a family and community that loved me. That love was made manifest in all kinds of ways. It was the wisdom Mary taught me and how she opted to walk back and forth to work to save up money, along with S&H Green Stamps, for the nice blanket she was determined to bring newborn me home in, after my six-month-plus stay in the hospital.

It was the example my granddad Olden set for me in everything from his quiet resolve to his commitment to keep my feet on that sidewalk. It was my mother marching through downtown Birmingham and getting arrested at 13. And it was the interracial staff of doctors and nurses at Children’s Hospital who cared for a constantly ailing little boy in late 1960s and ‘70s Birmingham, and who never allowed bigotry to enter that sacred space.

It was the elderly Anglo cashier at the supermarket where I, as an eleven-year-old worked, the one who constantly gave me shoes, shirts, etc. that she’d always bought for her grandsons. “I’ve lost the receipt and can’t return them,” she’d say every time. “Maybe you can try them on?” They always fit perfectly. And her retired husband who hired me to work on weekends at their house, pulling weeds, but we spent far more time on his hobby projects and eating cookies his wife had just baked.

I’ll never forget the looks that shifted from shock to indignation, to something resembling remorse, when, while walking down the sidewalk to the hardware store in a part of Birmingham that was still segregated by practice, he placed a protective arm around my shoulder like I was his own grandson; wordlessly daring anyone to object. They all taught me that ending bigotry is something we do every day of our lives.

I’d get to grow up seeing the spiritual ethos of the Civil Rights movement acted out all around me, then, in my college and divinity school years, see the gradual social radicalization of entire congregations who, like politicians and “states’ rights”, proclaimed, “We’re not against ‘you people’, we’re for the Bible.”

I’d see our racial and religious wrangling from every angle imaginable – from growing up a mile from the 16th Street Baptist Church and speaking in historically white churches on behalf of Richard Arrington’s storied run for Mayor on the one hand to being one of 400 African American students on a college campus of 20,000 and the sole African American male in my seminary graduating class.

I’d see so much of our history unfold in real time. I saw not just one but two mass exoduses as Southern Baptists continued to shrink the circle of their “we”. I saw the devastation of the AIDS epidemic while serving as a chaplain in San Francisco in the 90s, and how most Christian groups, with the notable exception of Catholic nuns, pretended those deaths either didn’t happen or didn’t matter.

I got to learn amazing lessons about courage, humanity, and yes, pride from those I had the honor of supporting. And to a person, while I took on that work to be helpful to them, turned out they were really the ones doing the helping. So much of who I am today is due to them.

I’d spend more than a decade living in New York, where I’d see both the beauty of true diversity and what the world looks like when not viewed through racialized lenses – something that comes naturally to New Yorkers, but not so much for the rest of us Americans.

Take, for instance, when Steven, a member of my “found” family, was hospitalized and I went to visit. “I’m his brother,” I matter-of-factly announced to the nurse, claiming this blond, pale-skinned Swiss-German mix as my kin. “Oh, great!” she said, without the slightest hesitation. “You guys’ other brother (Tom, Steve’s twin) was just by here earlier.”

Steve has congestive heart failure, and never, in all the times I showed up at the hospital did anyone ever look questioningly when I declared us brothers, which, we are. Then, there’s the way his family has adopted me right back; the birthdays they’ve celebrated, the Christmas gifts given and the way his mom describes me as “the son she got without having to go into labor.”

I’m grateful for how my growing up allowed me to play a unique role in the Obama campaign – reaching out to historically white churches across the nation the same way, as a boy, I’d done for Richard Arrington. I’m thankful for how, simply because I happened to be living in the Pacific Northwest (I moved here to undergo cancer treatment), I could help organize many of those same people as a Wall of Clergy – pastors, ministers, priests, nuns, rabbis, imams and others – who placed their bodies between Portland’s protestors and the federal troops called up by a sitting president.

And, I’m mindful of guys like George and Strom and Elwin, how they taught me that the only bigotry we can defeat is our own, and how none of us know how much time we have left to do the right thing. How we use today is the only thing we truly have control over.

“We are not makers of history,” Martin once said, “We are made by history.” And he was right. I especially grasp this today, when I can feel the history that’s made me, from Mary and Olden to the supermarket cashier and her husband, from those who sought to impede equality to the struggles that made me stronger, we all both carry our history and are carried by it. I can feel all these experiences swirling inside me right now, made all the more profound by where we are as a nation and by the fact that I never, in a thousand years, imagined I’d still be here to celebrate 60 years, having traveled from then to now.

But I am here, and that, combined with the path that led me here, to this moment, feels… something. I’m not sure what the right word is. But I know that, in some strange way, all the tributaries of my life meet here, and I can’t think of a better way to lead a life. Because, no matter what unfolds, people in the future will be talking about this time in American history long after we’re gone.

The nation we’ll end up becoming will be largely decided over the next 12 – 48 months. And you and I get to be part of that deciding. We might not be the makers of history, but we can sure as hell meet it. We don’t choose the times in which we live, but we do get to choose who we’ll be within them. And, all the more, in extraordinary times, at history’s arc points.

That’s where we are today. You and I didn’t get to emancipate a people or overthrow segregation. But right now the legacies of those who did are in our hands. We, by what we do or don’t do – right now – get to determine whether the uncompleted work of emancipation began by the Republican Party and the 60 years of unfinished business by the Civil Rights movement are annulled or finally brought to fruition.

If ever there was an “all hands on deck moment” for us, I believe this is it. As much as any time in our nation’s history, what you and I do matters. We get to decide whether we’ll be a nation that merely stops looking like we’re bigoted or whether we’ll actually, finally, leave it behind and reach for something better. But, if there’s anything that 60 years of being on the receiving end of such good will has taught me, it’s that we can handle this. We’re a people that’s repeatedly found the strength and the fortitude within ourselves to do something extraordinary. To rise. It’s going to be an amazing thing to see.

The song on my mind when I woke up this morning was Rise Up by Andra Day:

You're broken down and tired of living life on a merry-go-round. And you can't find the fighter, but I see it in you, so we’re gonna walk it out. And move mountains. We’re gonna walk it out. And move mountains.

And I’ll rise up, I’ll rise like the day. I’ll rise up, I’ll rise unafraid. I’ll rise up, and I’ll do it a thousand times again.

All we need, all we need is hope. And for that, we have each other, and for that, we have each other. We will rise, oh, we’ll rise.

And we’ll rise up, high like the waves, we’ll rise up, in spite of the ache, we’ll rise up, and we’ll do it a thousand times again.

I can’t imagine a more perfect thought right now. Because rising up is exactly what we’ll do. And for me, on this 60th birthday, there’s no place I’d rather be, or time I’d rather live in. This, right here, is how I want to spend all the days I have left, right now, with you, meeting history.